|

The Backstory | NICOLE CARROLL SHARES OUR STORIES OF THE WEEK - AND THE STORIES BEHIND THEM | Friday, September 24 | | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| I'm USA TODAY editor-in-chief Nicole Carroll, and this is The Backstory, insights into our biggest stories of the week. If you'd like to get The Backstory in your inbox every week, sign up here. |

| The civil rights legends were dying. |

| John Lewis, C.T. Vivian and the Rev. Joseph Lowery all passed away in 2020, Lewis and Vivian on the same day. |

| USA TODAY reporter Deborah Berry has been covering civil and voting rights for most of her career. But now she felt pressure, more so, she felt responsible to share more of their history before the history makers were gone. |

| "It was like, man, if we don't tell their stories, and if we don't tell them now, when do we tell them," Berry said. |

| | Charlayne Hunter, 18, the first Black woman to attend the University of Georgia, sits in one of her classes in Athens, Ga., on Jan. 11, 1961. The students at right are unidentified. Hunter and 19-year-old Hamilton Holmes began classes that day under court order. | | AP | |

This thought sparked the USA TODAY project that launched this week, Seven Days of 1961, a look at seven events that fueled the civil rights movement and their impact today. The project continues throughout the year. |

| "Even while working on this project, we were losing veterans. People who we had reached out to talk to passed away," Berry said. "I got off the plane in Mississippi and one of the legends died that day." |

| Berry had hoped to interview Robert "Bob" Moses, a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who worked to empower Black people in Mississippi through voter education efforts and voter registration drives. She was in Mississippi to talk to a friend of his, civil rights activist Hollis Watkins, when she got the news. |

| Berry and visual journalist Jasper Colt were five minutes away from Watkins' house when his wife told them he couldn't talk, he had just lost one of his best friends. |

| "It just hit home that even in the midst of working on this they were leaving us and we could no longer tell their stories" from their perspectives, Berry said. |

| Nearly every few weeks in 1961, there were battles for voting rights and integrating schools, businesses and libraries. Our team focused on seven crucial days, interviewing those who lived through the protests, asking them to share their stories in their own words. Reporters also sought out those who helped in the background, like the people who fed, housed and drove the protesters. |

| "It happened to be a year when a whole lot happened," Berry said. "Especially with SNCC going into places like Mississippi, especially with other groups going into places like southwest Georgia. The more we talked to veterans, they talked about what they did in '61 and how that influenced things later on. So it became a good year to look at." |

| | USA Today journalist Jasper Colt photographs Hezekiah Watkins as he sits for a portrait in a recreated jail cell in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. | | Deborah Berry, USA TODAY | |

Connecting 1961 to 2021 was critical for project editor Cristina Silva. The battles fought in 1961 are not yet over. Young people then were fighting for progress, as are young people today. |

| "The young people (of 1961) told us over and over again that they saw the lives that their parents had lived and they didn't want that to be their life," said Silva, deputy managing editor for news. "And I hear that in the young people today. We see a lot of generational discourse about what is acceptable in America. We hear from a lot of young people, this is not enough progress for us." |

| In 1961, there were fights over school integration. In 2021, there are fights over teaching about oppression and racism. |

| Sixty years ago, protesters were beaten, jailed and could be put on chain gangs. In 2021, as we continue to grapple with police violence and the role of police in our communities, a handful of states have passed anti-protest laws. |

| In 1961, activists marched for voting rights. In 2021, they march against voting restrictions. |

| "You can see it when we talk about the media then and now, the way that the media covers people of color, the fact that the media disproportionately remained so white," Silva said. "There are so many threads." |

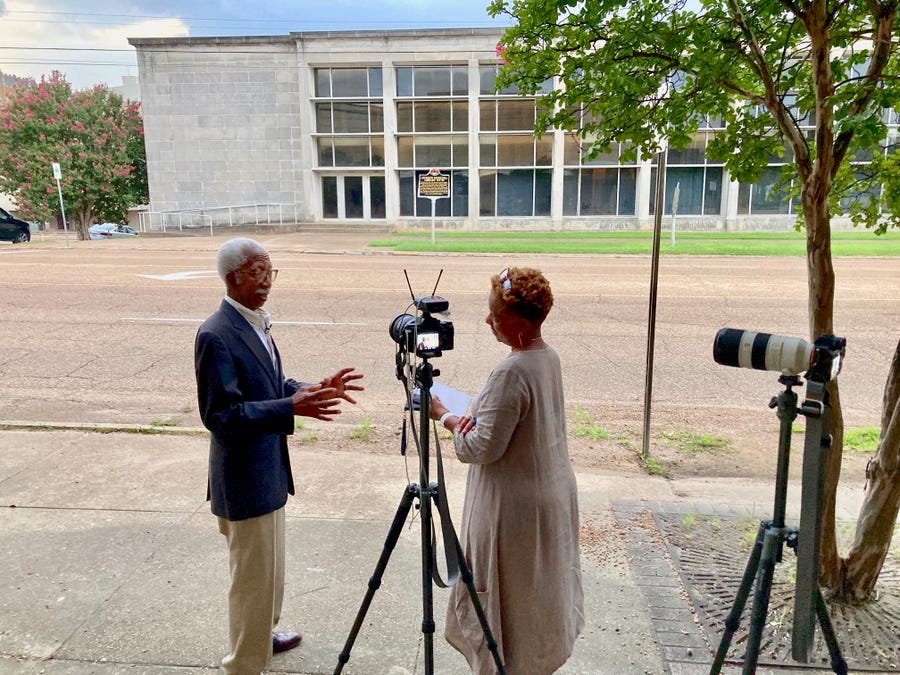

| | USA TODAY journalist Deborah Berry, right, speaks with Jerry Keahey, who drove the Tougaloo Nine in 1961. | | Jasper Colt, USA TODAY | |

The reporting was emotional for the subjects – and for the journalists. As the civil rights pioneers told their stories, our team witnessed pain as real today as it was in 1961. |

| In Jackson, Mississippi, Berry and Colt were standing outside the public library that had been the scene of a "read-in" on March 27, 1961. Nine students from Tougaloo Southern Christian College, a private, historically Black school outside Jackson, dared to walk into the whites-only library. |

| They became known as the "Tougaloo Nine." They had prayed for safety before loading into a yellow and white station wagon for the drive into town. The Ku Klux Klan was terrorizing Mississippi, Black churches were bombed and the state had one of the highest numbers of lynchings in the country. |

| Fellow student Jerry W. Keahey Sr. took them to the library that day. Keahey had no idea what would happen to his friends after he dropped them off. |

| "He was a stately gentleman, old school, real warm, like your grandfather and you just talking," Berry said. "And then he talked about when he had to leave them because his job was to be the driver and drop them off and leave. |

| "He was pointing to the building and he choked up because he had to leave them, he had to drive away and leave those nine students and not know what happened to them. And he was scared, not just for himself, but for those folks he was leaving behind. And I just thought how that must've felt, to be brave enough to do it, but to not be able to protect your school mates. Not to know if they would be lynched, hung, beaten, whatever. He was choking up and we were almost choking up, too." |

| | This photo shows the nine Tougaloo College students who held the first "read-in" in Mississippi when they attempted to desegregate the all-white Jackson Public Library. Their action and subsequent arrests drew the attention of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, the now-defunct segregationist spy agency, which kept tabs on the students, faculty and administrators. The Tougaloo Nine are, from left, Joseph Jackson, Geraldine Edwards, James Cleo Bradford, Evelyn Pierce, Albert Lassiter, Ethel Sawyer, Meredith C. Anding Jr., Janice L. Jackson and Alfred Lee Cook. | | Courtesy of Tougaloo College | |

| Berry didn't always want to be a journalist. But her high school English teacher, Patricia Tuitt at Brooklyn's Boys and Girls High School, saw her talent and "made her write stories." |

| "And then once I stepped into the world of journalism, it became what I was passionate about and still love to do," Berry said. |

| "Thank God for that teacher," Silva chimed in. |

| "Ms. Patricia still checks in on me by email every once in a while to tell me what I should have done with a story," Berry said, laughing. |

| FREE EVENT: A conversation on civil rights: Join USA TODAY to discuss community leaders' roles in helping fight systemic racism |

She also credits the civil rights veterans she's writing about today for making her career – and the careers of so many Black journalists – possible. |

| Twelve years ago, Berry and the late Maria Fowler, a videographer, went to talk with Lawrence Guyot, who devoted his life to making sure Black people in Mississippi and across the country could vote. When Berry called to request the interview, he didn't sound well. She asked, "Are you sure you want to do this?" |

| "He said, yeah, yeah, come on," Berry said. "So we went over there and we were asked to wait outside a little bit because somebody was in the house, and come to find out it was a hospice nurse. He was dying, but no matter what he wanted us to come on in there in his kitchen and talk to him about Mississippi, about the fight for civil rights in Mississippi. |

| "And I remember that because I'm thinking here he is telling his story on his way out and not letting that stop him from doing it. That always stuck in my heart, because I felt like if he wanted to tell his story, there must have been so many others wanting to tell theirs, too." |

| She ended up visiting him in the hospital in his final days. She thanked him for paving the way for her and so many others. He simply nodded. |

| The Backstory: Long COVID causes fatigue, pain. Here's what long-haulers want you to know. |

| The Backstory: Afghan journalists are being held and beat in Kabul. Here is their story. |

| Nicole Carroll is the editor-in-chief of USA TODAY. Reach her at EIC@usatoday.com or follow her on Twitter here. Thank you for supporting our journalism. You can subscribe here. |

| |

| |

| |